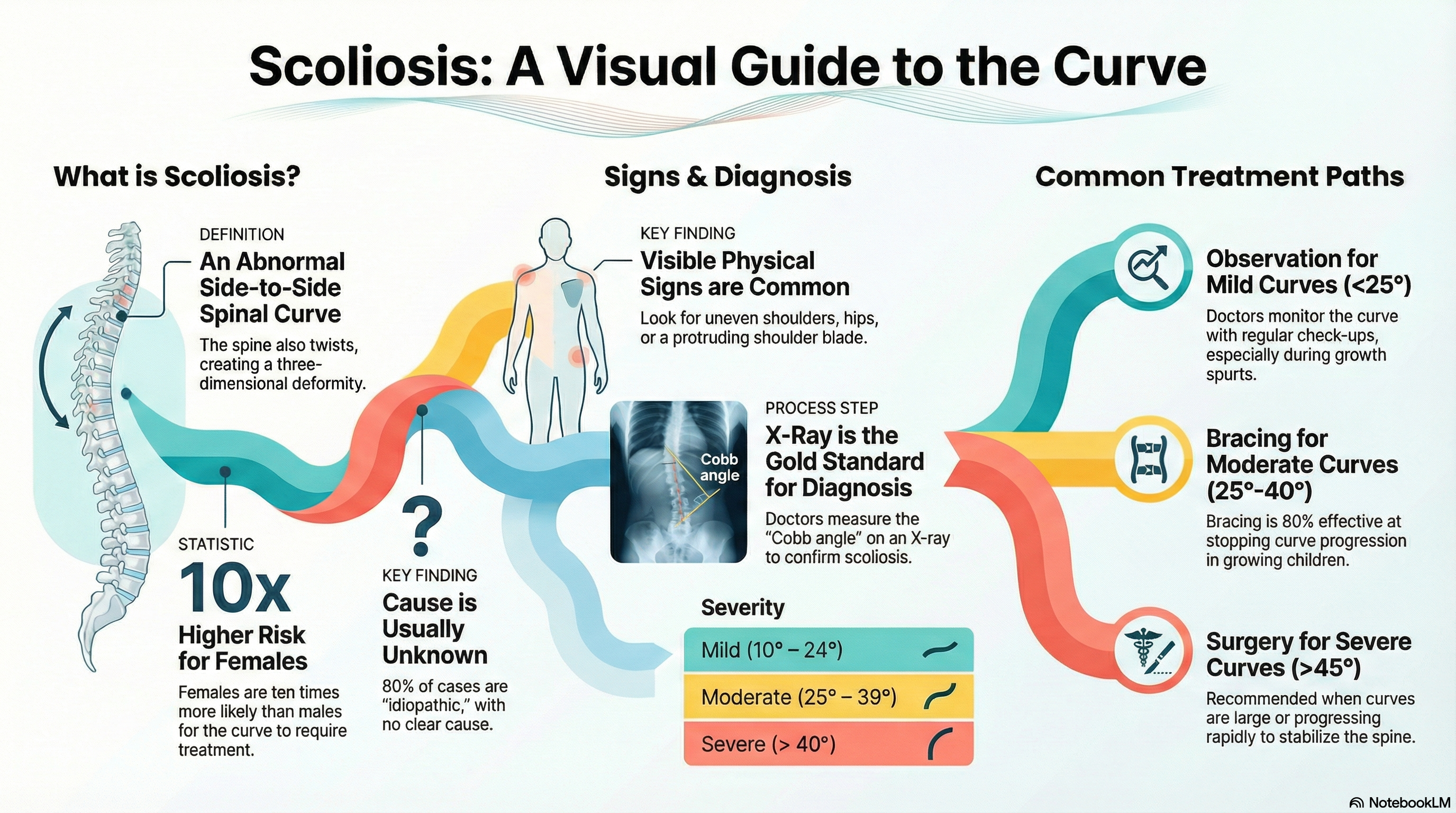

What is Scoliosis?

Scoliosis is a structural condition where the spine develops an abnormal side-to-side (lateral) curve, often taking on a "C" or "S" shape. While the spine has natural front-to-back curves, scoliosis involves a three-dimensional deformity, meaning the vertebrae (the bones of the spine) may also rotate or twist.

A definitive diagnosis is made when the curvature, known as the Cobb angle, measures 10° or more on a standing X-ray. It affects approximately 2–3% of the global population. While it can affect both males and females equally, females have a significantly higher risk—up to 10 times greater—of the curve progressing to a point where treatment is required.

Common Types

-

Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis (AIS): The most common form (80% of cases), appearing between ages 10 and 18. "Idiopathic" means the exact cause is unknown.

-

Congenital Scoliosis: Present at birth due to a failure of the vertebrae to form correctly during embryonic development.

-

Neuromuscular Scoliosis: Resulting from conditions that affect the nerves and muscles, such as cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy.

-

Degenerative Scoliosis: Occurs in adults (typically over age 40) due to the wear and tear of spinal discs and joints over time.

Causes of Scoliosis

In the vast majority of cases (idiopathic), the cause remains unknown. However, researchers have identified several factors that contribute to the condition:

-

Genetics: Scoliosis often runs in families, suggesting a strong hereditary link, though no single "scoliosis gene" has been identified.

-

Growth Spurts: The most significant changes usually occur during the rapid growth phase of puberty.

-

Neuromuscular Conditions: Nerve or muscle disorders can pull the spine out of alignment.

-

Degeneration: In older adults, osteoporosis and joint breakdown can cause the spine to shift.

Note: Contrary to common myths, scoliosis is not caused by poor posture, carrying heavy backpacks, diet, or specific types of exercise.

Symptoms of Scoliosis

Mild scoliosis often goes unnoticed because it is rarely painful in children and adolescents. It is frequently first identified during school screenings or sports physicals. Visible signs include:

-

Asymmetry: Uneven shoulders, waistline, or hips (one side appears higher than the other).

-

Protrusion: One shoulder blade or one side of the rib cage sticking out more than the other.

-

Off-Center Alignment: The head may not appear centered directly over the pelvis, or the entire body may lean to one side.

-

Physical Discomfort: While less common in teens, adults often experience back pain, leg numbness, or a loss of height.

-

Severe Complications: In rare, extreme cases (curves >70°), the rib cage may press against the lungs, causing shortness of breath or diminished lung capacity.

Diagnosis of Scoliosis

Early detection is vital, particularly during the growing years. Diagnostic steps include:

-

Physical Exam (Adam’s Forward Bend Test): The patient bends forward at the waist. The doctor looks for a "rib hump" or any asymmetry in the back or trunk.

-

Scoliometer Measurement: A tool used during the bend test to measure the degree of trunk rotation. A measurement of 5–7° typically prompts a referral for imaging.

-

X-ray Imaging: Standing X-rays are the gold standard. They allow doctors to measure the Cobb angle to determine the severity:

-

Mild: 10–24°

-

Moderate: 25–39°

-

Severe: >40°

-

-

Neurological Testing: A doctor may check reflexes and muscle strength to rule out underlying nerve issues.

-

MRI: Reserved for cases where an underlying cause—like a tumor or spinal cord abnormality—is suspected.

Treatment of Scoliosis

Treatment goals are to prevent the curve from worsening, improve appearance, and alleviate discomfort. The choice of treatment depends on the curve’s degree and the patient’s remaining growth potential.

-

Observation: For mild curves (less than 25°), doctors typically recommend "watchful waiting" with follow-up exams every 4–6 months to monitor for progression.

-

Bracing: For moderate curves (25–40°) in children who are still growing, a brace can be used. Bracing does not "fix" the curve, but it is roughly 80% effective at stopping it from getting worse. Modern braces are often worn 13–23 hours a day.

-

Physical Therapy: Specialized exercises (such as the Schroth method) can help strengthen the core and improve posture, though they generally do not stop curve progression on their own.

-

Surgery: Reserved for severe curves (usually over 45–50°) or those progressing rapidly.

-

Spinal Fusion: The most common surgery, using rods and screws to stabilize and straighten the spine.

-

Vertebral Body Tethering (VBT): A newer, "growth-friendly" option for some children that preserves more spinal flexibility.

-

Prevention of Scoliosis

There is currently no known way to prevent the onset of scoliosis, as most cases are idiopathic or congenital. However, you can manage the condition and its impact through:

-

Early Screening: Regular check-ups during the pre-teen and teenage years are the best way to catch curves early when non-surgical treatments are most effective.

-

Active Lifestyle: Staying active and maintaining a strong core is highly encouraged. Swimming is often recommended as a low-impact way to support spinal health.

-

Bone Health: A healthy diet rich in Vitamin D and Calcium is important, especially for adults, to prevent bone density loss that could worsen a curve.

-

Support Systems: Because scoliosis can affect body image and self-esteem, especially in teenagers, support groups and counseling can be a valuable part of the overall care plan.